It’s good to see you! Before we begin, a little reminder that my next adult book, City of Orange, is coming out May 24. (It’s a different kind of post-apocalyptic story.)

I have a handful of advance reader copies (ARCs) in my closet, so I’ll mail free signed copies to whoever hits me up first. Quantities are limited and is exclusive to you guys because you actually care enough to read this newsletter. 🤪

Let’s begin! This newsletter is all about story tropes and story structure. First, let’s talk about story types.

Story Tropes (or everything is formulaic)

People often complain that Everything’s so formulaic and It’s all been done before. The thing is, they’re not wrong! Most stories you see can be shoehorned into a narrative trope. Here’s a few:

Man vs. Man

Man vs. Nature

Man vs. Society

Man vs. Self

Man vs. Technology

And some more!

Adventure

Action

Horror

Thriller

Mystery

Romance

Coming of Age

And let’s not forget YA tropes!

Dystopia

The Chosen One

The Outsider

Love Triangle

Traumatic Pasts

Dangerous Game

Dangerous Adults

Fake Dating

Enemies To Lovers

Accidental Royalty

Every type of story has been told, and that’s okay. That’s because what the story is is less important than how the story is told. The what of a story is limited. The how, on the other hand, is infinite.

You can think of a pie as a formula or trope defined as stuff baked inside a crust. Yet there are so many different pies! That’s because there are infinite ways to bake them. Even in the “sub-trope” of apple pie, there can be many variations.

Story structure: the invisible blueprint

People also sometimes complain about certain events happening over and over in stories. The big chase scene at the end of a rom-com. The mano-a-mano at the end of an action flick. They call these things formulaic, too.

And they’re right! Stories (at least in the modern Western tradition) tend to follow the same arc again and again, following the formula of a three-act story structure.

But here’s the thing: most readers wouldn’t have it any other way. As much as they might complain about the three-act structure’s predictability, they’d probably find a story awkward if it deviated or ignored big parts of it. There are of course great stories that ignore this formula (including your typical Japanese story), but they’re by far the rare exception rather than the norm in modern Western media.

I love the three-act formula. I love it so much that I track story progress using sticker dots on my TV:

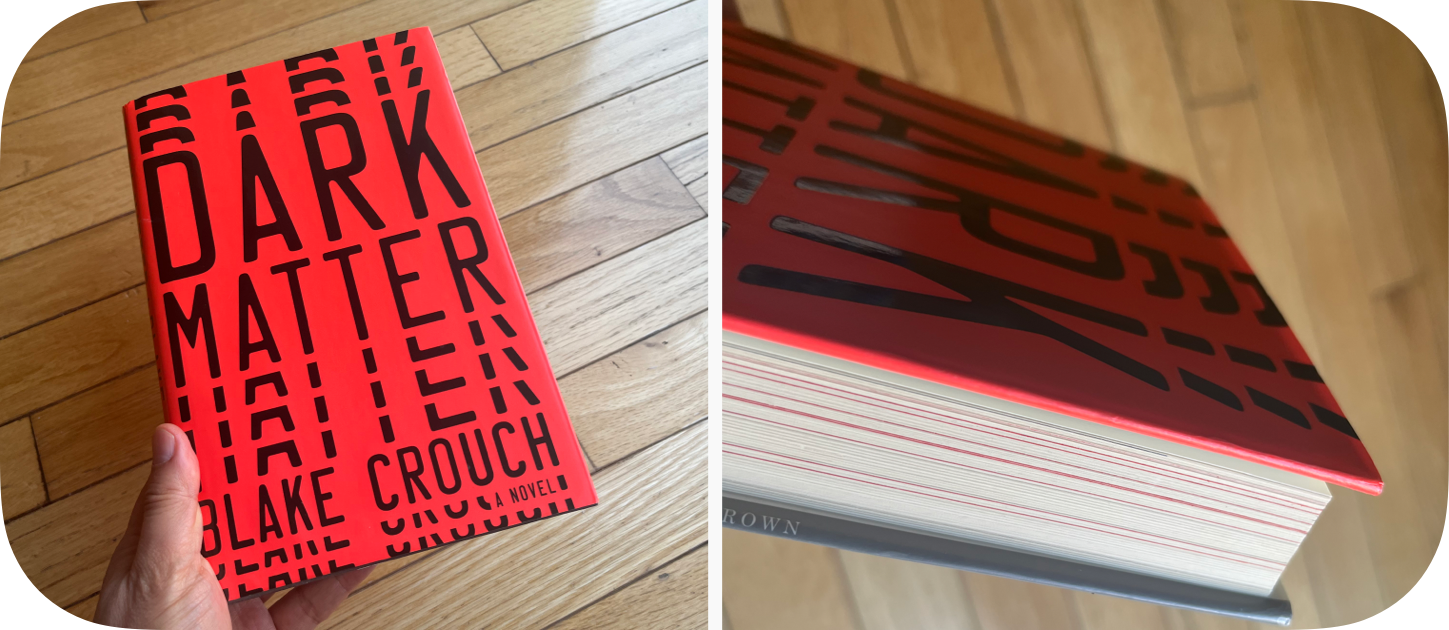

I also like to mark story progress in books by marking the edges in red Sharpie. Here’s one of my favorites, Dark Matter by Blake Crouch:

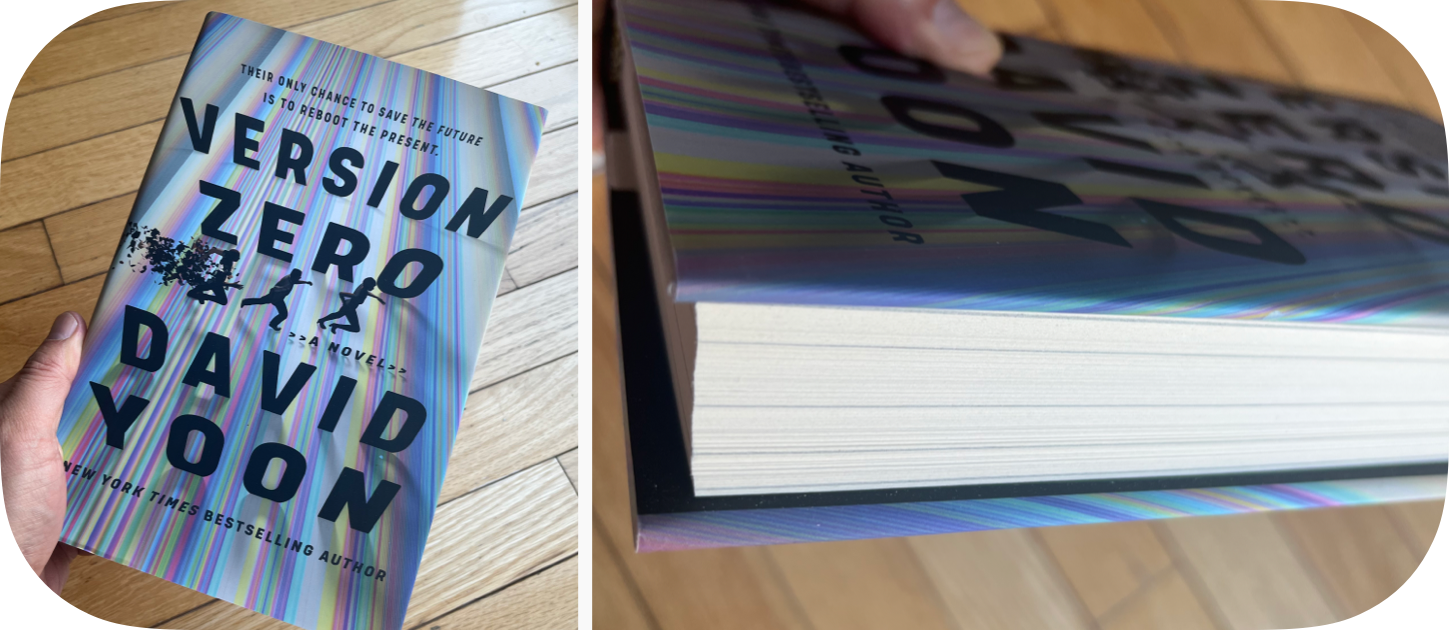

My own book, Version Zero, happens to have story structure conveniently marked by design. See the light gray lines?

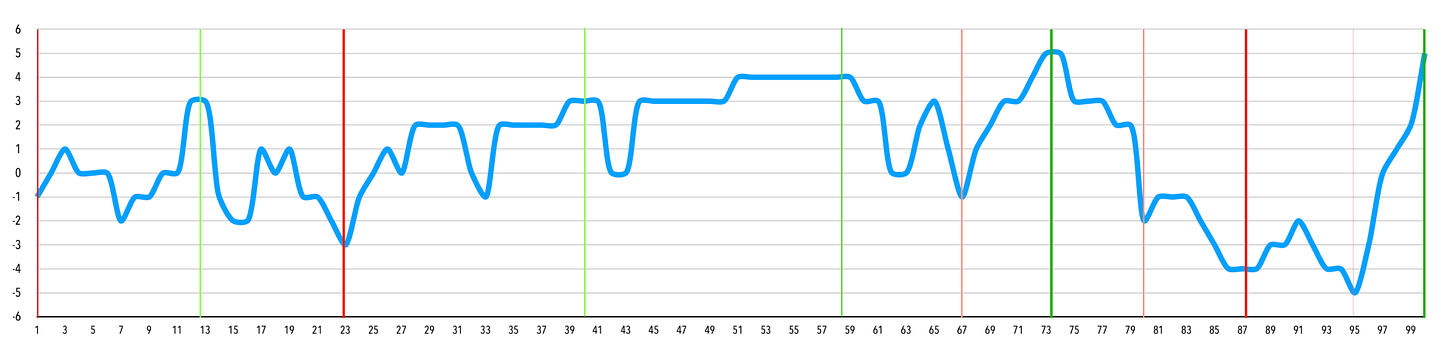

I also like to map out my favorite movies minute-by-minute…

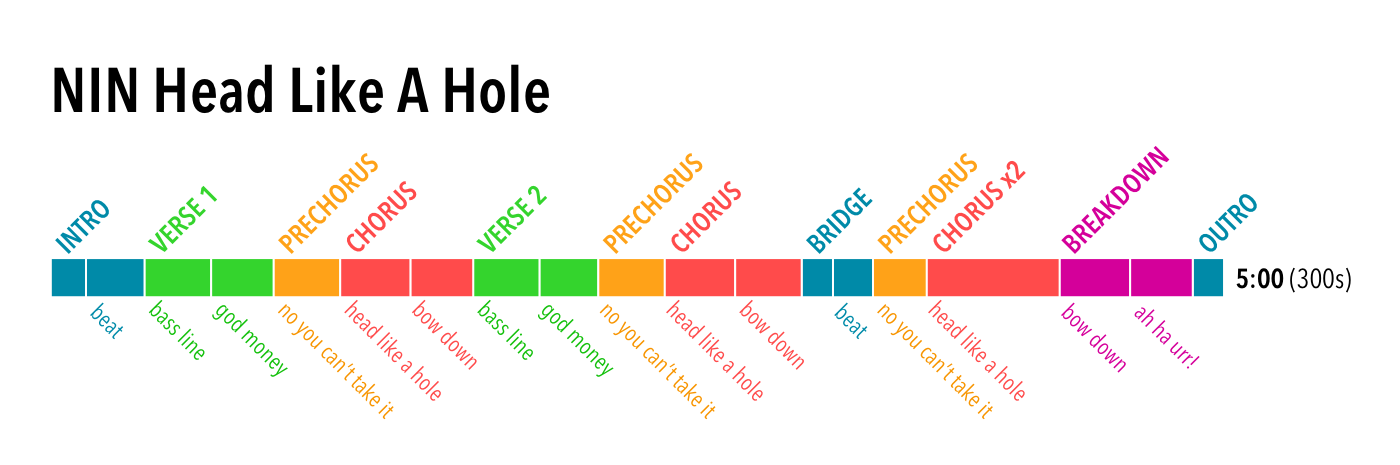

…and (slight tangent here) even my favorite songs:

I acknowledge I have a problem.

There’s freedom in formula. (No, really!)

In a nutshell, the three-act structure does a few key things:

It ensures something interesting happens at least every eighth (1/8th) of the book. That’s every 44 pages for a 350 page book. Keeps you reading!

It ensures that all action is constantly escalating in magnitude. You never get bored, and the steady rhythm keeps your expectations engaged!

As a writer, it frees my brain up to think about character and plot development. I know my hero has to hit certain emotional highs and lows. Instead of having to focus on plot structure, I can focus on the plot details instead. So useful!

You can look at formula as a useful limitation, which is an artist’s best friend. Setting rules for yourself frees you from having to pick and choose tools and instead just focus on using the tools you have. It’s less intimidating to start drawing with a ball point pen than with two thousand color markers.

So what is the three act structure?

There’s lots of models of the three-act structure (just do a search), but I’ve drawn my own basic model that I keep in my head below. Notice how the length of the story is chopped in half, then half again, then half again. At every quarter, something interesting happens. In lots of stories, it’s every eighth. In really good stories, something interesting happens at every sixteenth. (Interestingly, this even splitting also occurs in music, but that’s another newsletter.)

The rising and falling line represents our emotional state as readers. As it rises, we feel happier and happier for our heroes. As it falls, we feel sadder.

Try your best to be keenly aware of how a book is making you feel, and when. When do you feel happy or sad? Thrilled, scared, or amused? Chances are those emotional moments are happening at regular intervals.

Let’s break it down!

ACT 1 — Welcome to the world

Intro: We meet our hero, learn what they want, and the rules of the world they’re living in.

Inciting: Something drastic happens that forces them to act.

Decision: The hero must embark on a journey from which they can’t return, in order to get the thing they want most. This marks the boundary between Acts 1 and 2. Books will often have a blank page as an act break at this point, to really emphasize that the hero has entered a new world. Movies will often literally fade to black for a moment.

ACT 2 — The journey

Once our hero has embarked on their journey in Act 2, they’ll encounter some minor bumps as they learn the ropes of this new world. These trials culminate in the hero’s first Minor Success.

A Minor Setback immediately follows this success, though. That’s because you can’t stay on an emotional high for too long—people crave tension and struggle! A story where everything goes smoothly is boring.

As the hero masters their new world, they reach a Major Success…

…almost immediately followed by a disastrous Major Setback. The story takes a pause here to let the reader really take in the direness of the situation before heading into Act 3.

(Notice how the highs are constantly getting higher and the lows lower? That’s because our brains tend to normalize emotional baselines. It would feel weird if our hero found the treasure of their dreams and then learned the basics of swordfighting.)

ACT 3 — The path to victory

The hero must now claw their way toward a final Victory using everything they’ve learned over the course of the story. (Sometimes along the way there’ll be a fun twist, usually halfway through Act 3.) I use the word Victory here because, let’s be honest, the vast majority of stories have happy endings (because people love happy endings).

After the Victory there’ll be an End (or denouement if you’re fancy). This is usually short. The hero got what they wanted—what else is there to say?

Great! So now what?

Now you have a nifty blueprint! Next you need to figure out what story to tell. If you’re stumped, maybe pick one of the story types we talked about. Like a rom-com! You can even pick a well-known rom-com trope like enemies-to-lovers. Combined with a basic three-act structure, you now have a basic what for your story.

But what about the how? That really depends on what your hero wants, and what their deep-seated personal problem is. It depends, in other words, on their central dramatic question. I think I’ll talk about that in the next newsletter.

For now, mark up your books and put stickers on your TVs. You’ll be surprised at how the emotional moments tend to line up in the same spots again and again. You’ll also become the most annoying person to watch movies with! Just ask Nicki!

Thanks for reading. In a world of cheap social media likes, you guys are my true community.

— Dave

Remember, City of Orange comes out May 24. Hit me up and I’ll send you a signed ARC. ❤️

This was a great newsletter, thank you so much for the advice!!

As soon as Rob and I read about your system, we raced to our bookshelf and delighted in the gray lines on the pages of Version Zero! Feels like finding a 'hidden Mickey' :) Thank you for sharing your splendid system and for bringing pie to the writing craft table! May we also request an ARC of City of Orange?